From the First Three Minutes to Us

One of the past century’s greatest scientists, Steven Weinberg, died last week amid worldwide acclaim. He wasn’t famous like Einstein or Stephen Hawking, but he probably did more to explain and unify notions about the fundamental constituents of matter and the origins of our universe than any other recent figure. And unlike many scientists, he could write – for technical audiences as well as for general readers. He rightly received a Nobel Prize in 1979. Weinberg stayed active in research and teaching until shortly before he died, a fitting finish for an amazingly productive life – but also a tragic life of cosmic proportions.

His death sent me back to his most famous book: The First Three Minutes. I began university as a physics student. My turn into whatever I am now was, for my father, puzzling. Physics he understood. Liberal studies, he thought, were for rich people who didn’t need to earn a living. At some youthful moments, I almost thought he was right. But in my dotage, I suspect a hidden hand guided me – as it guided Socrates from his early interest in materialist science to philosophy, though with infinitely more modest results. My look back into The First Three Minutes confirms that it was right, for me, to turn elsewhere.

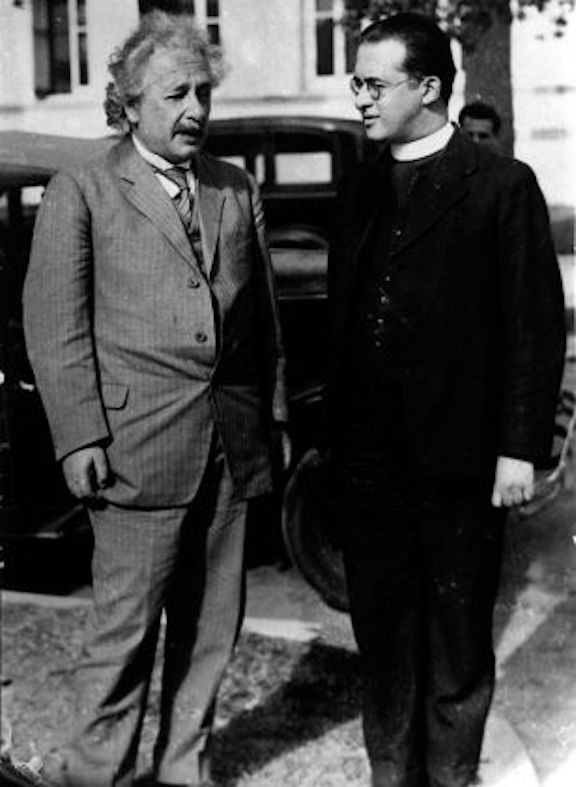

That book, as the title indicates, is a popular account of the beginnings of the universe. (Let us leave aside for the moment how to understand those “minutes” since, as St. Augustine was aware long before Einstein, time itself comes into being with space and, therefore, the nature of time is not easy to specify.) The book is a lively portrayal of the stages scientists believe the universe passed through. From the Big Bang (first postulated in 1927 by the Belgian priest Georges Lemaître) to 10-43 sec. – so-called Planck Time. If you’ve forgotten the math, this means:

1 sec. /10 followed by 43 zeroes

An inconceivably short time.