Grandparents, Great-Grandparents, and the Great Tradition

Pope Francis inaugurated a new celebration in the Church yesterday, The World Day of Grandparents and the Elderly. He has spoken frequently in the past about the wisdom and experience of older persons. And the need to listen to them and be with them. He apparently thinks the theme so important that not only has he declared it a recurring observance on the fourth Sunday of July, he has even arranged for there to be a Plenary Indulgence – remission of all temporal punishment due to sin, under the usual conditions of Confession, Communion, prayer for the pope’s intentions, and so forth. In an age that is rapidly and universally losing touch with its past and, therefore, is unsteady about the future, it was an inspired idea.

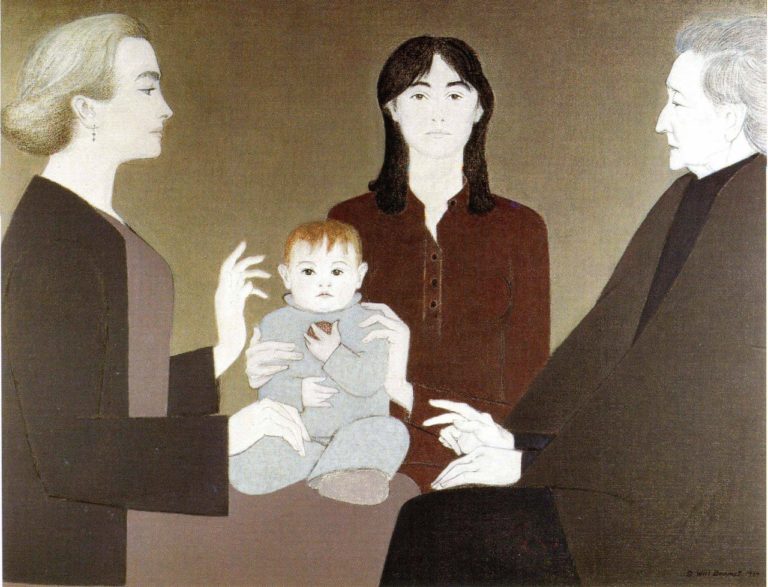

Many of us of a certain age remember living with, or close to, grandparents – in my own case even great-grandparents. They were a living chain to past challenges and success in overcoming them: such as immigration to a new country where they were discriminated against and didn’t know the language; World Wars I and II; the Great Depression; poverty and crime; the civil-rights struggle – and all within a context where help came from extended families, or not at all. And no whining. Everyone had problems and there was just too much to do.

I can’t say I learned a lot directly from a large extended family – I was young and typically foolish. Indirectly, I realized that I had been born into something larger than myself. Larger even than them. As large as the world.

The concrete results, generally, were what the late great British Rabbi Sir Jonathan Sacks called “adaptation without assimilation.” A society and a religious tradition – if they are alive – must face new moments. That is what it means to be beings in time, whose arrow runs in only one direction. But to negotiate those adaptations successfully means to remain rooted in one’s deeper identity.