Beauty Will Save the World

Written by Robert Royal

Tuesday, September 26, 2023

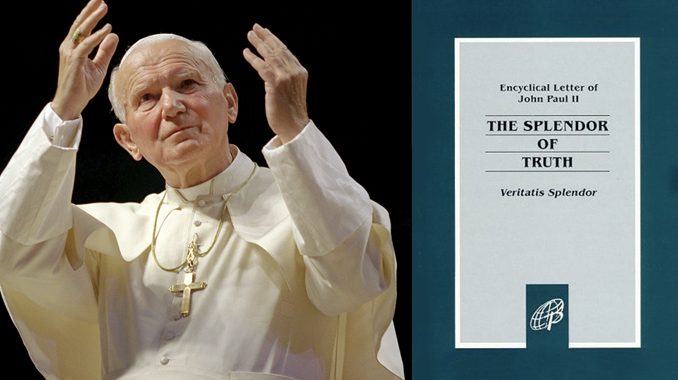

At least the above has been suggested by some very great Christians – Dostoyevsky (or at least his Prince Myshkin in The Idiot), Solzhenitsyn, St. John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and (in various ways) countless others. As Christians, they knew, of course, that God has saved the world, in the strong sense. And only He could. So what could they possibly mean?

Well, it may have much to do with some particularities of modern times. In his Nobel Prize address, Solzhenitsyn raised that specific question on the basis of the “three transcendentals”:

[P]erhaps that ancient trinity of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty is not simply an empty, faded formula as we thought in the days of our self-confident, materialistic youth? If the tops of these three trees converge, as the scholars maintained, but the too blatant, too direct stems of Truth and Goodness are crushed, cut down, not allowed through – then perhaps the fantastic, unpredictable, unexpected stems of Beauty will push through and soar TO THAT VERY SAME PLACE, and in so doing will fulfil the work of all three?

That’s a very hopeful way to look at things today. We know that Truth and Goodness are as confused now as they have ever been. And that while the slow process of reason recovers them both, some way around the impasse has to be found in the meantime. And yet, beauty (small “b”) is also often deceptive and seems more likely to wreck the world, absent faith and reason.